Edith Brinn Wharton

Para-Legal Specialist, Regional Attorney’s Office

Born on a sugar cane compound in Aguirre, Puerto Rico, Edith Brinn was destined to leave the United States Commonwealth to accept a position as a Government Girl in the 1940s. When Edith, the fifth of nine children turned 12 years old, Jaime Brinn, a widower, made an unconventional decision to send Edith to high school ahead of her older two brothers. Jaime knew it was important for women to be educated and could not afford to pay tuition for three children at once. He decided to invest in Edith’s education by sending her to high school, and she became the first child in the family to attend high school.

A year later, her two older brothers followed her to high school. Jaime Brinn accelerated Edith’s academic endeavors by sending her to high school, and invested in her vocational future by insisting she take typing and shorthand. Acquiring secretarial skills in high school paved the way for her to take advantage of federal clerical positions when the posting became available to qualified applicants.

Video of Aguirre, Puerto Rica, Edith Brinn’s home town. CLICK HERE for more photos.

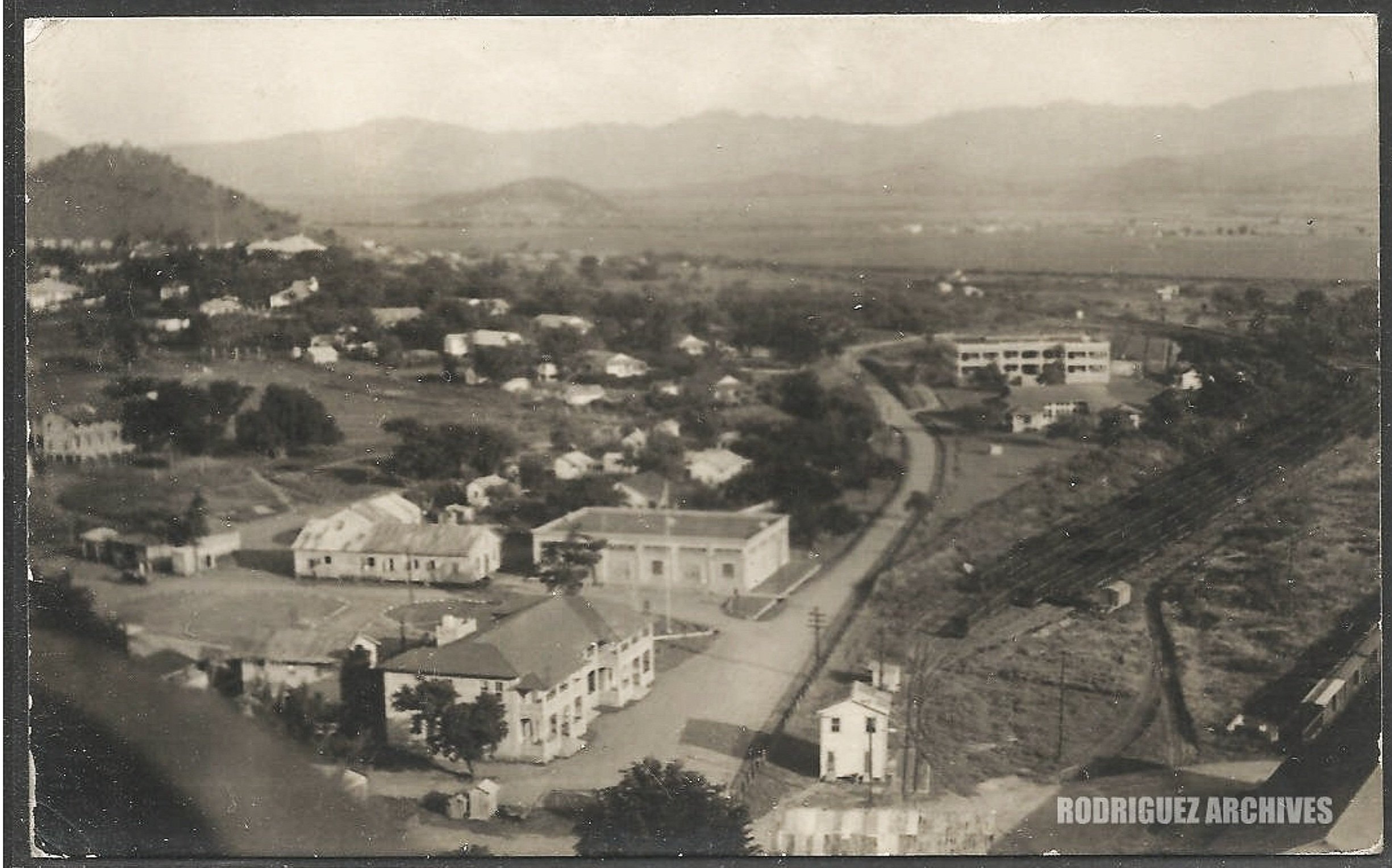

Bird’s Eye View of Central Aguirre, Puerto Rico — Post card mailed on Feb 11, 1935. Central Aguirre was a company town. The company owned the sugar mill, railroad, hospital, hotel, theater, stores and homes.

With Jaime’s blessings, Edith took the federal civil service written, typing, and oral English fluency test. A few weeks later, the results of the exam arrived in the mail. She passed all three tests with flying colors and became eligible to apply for work in Washington, DC. Edith accepted the appointment and prepared to travel to Washington, DC. It was unusual during the 1940’s for a young, unmarried girl to leave the comfort and support of the sugar cane compound. Edith would be the first of the nine Brinn siblings to leave the island of Puerto Rico to head to the mainland. The expression, “se embarcó” (s/he took a ship), told a story about Edith and others moving from Puerto Rico to other places in the United States to find work.

Class picture of Edith Brinn’s school in Aquirre

Edith Brinn walking to work in DC.

Edith Brinn in Midway Hall Dormitory in DC.

Edith’s arrival in the nation’s capital started the next chapter in her life. Luckily, she had been able to find housing in the Black, all-women’s residence dormitory of Midway Hall. Strict rules regarding social behavior, housekeeping, and visiting hours for male guests, helped to maintain a decorum of respectability. Male guests were restricted to the first floor sitting room. Couples conducted their courting rituals under the vigilant eye of the housemother. Weekday and weekend curfew hours were strictly enforced. Any breech of the contract was cause for dismissal from the dorms.

Friendships helped to manage the hardships associated with language differences and Edith’s isolation from family members in Puerto Rico. It is likely Edith did not have a network of Puerto Rican women to engage in any discussions about the challenges of living and working in a new city with unfamiliar rules and social barriers. In the absence of a Latina circle of women to soften the blows of isolation and racial indifference, Edith formed new alliances with the other women of color. She recalled the friendships formed while living in the dormitory and often referred to Slowe and Midway Halls as her safe haven. Once Edith settled into her living quarters at Slowe Hall and a work routine at the Pentagon, she began to polish her English skills by listening to conversations among her dorm mates. Edith formed an invincible bond with the African American government girls who lived in Slowe and Midway Halls. Residents in Midway Hall eagerly embraced her as one of their lost sisters of Diaspora. Edith often remarked that as an Afro-Latina, she remained committed to learning about the African American culture while maintaining her Puerto Rican roots.

Edith lived in Slowe Hall until she married Donald Wharton, a Howard University international undergraduate student from British Guyana. In June 1953, Donald and Edith exchanged wedding vows at Rankin Chapel. For the next 20 years, Edith’s steady employment with the federal government enabled Donald to complete his undergraduate and graduate degrees. Donald, a “professional student,” became a master at holding down full-time employment while attending post graduate programs. Late at night over the span of 15 years, it was not unusual to hear the sound of a Royal typewriter as Edith typed Donald’s two graduate theses and a doctoral dissertation. Donald, grateful and proud of his wife’s editing and typing skills, publicly acknowledged his academic and professional accomplishments by always crediting his wife and soulmate, Edith.

Dr. Donald Wharton became a public-school principal in the 1970s. He died in 1980. A year after his death, the State of Illinois acknowledged his distinguished career as an educator and public servant by re-naming Argo Community School as the Dr. Donald E. Wharton Elementary School. Edith and her four children, Carmen, Donald Jr., Lloyd, and Aura, stood proudly to accept the honors.

Edith held several clerical positions in governmental agencies including the Pentagon, the War Assets Administration (Philadelphia, PA), Department of the Navy (DC), the Department of the Army, TAGO (DC), the QM Food and Container Institute, the Corp of Engineers' Chicago Procurement Office, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the Regional Attorney’s Office. The 1970s provided Edith with the opportunity to return to school at Kennedy-King College, in Chicago. The college awarded her an academic scholarship to pursue a degree in Spanish. Edith graduated with honors in Bilingual Education in 1976. The attorneys in the Regional Attorney’s office encouraged her to enroll at Roosevelt University to earn a certificate in Paralegal Studies in 1979. With her vast experience working in the federal sector and the dawn of the age of computers, Edith became an invaluable asset to the attorneys in the department. Edith Brinn Wharton died in 1993.